Plastikman and Chilly Gonzales – Consumed In Key

(Turbo Recordings, 2022-04-01)

In walks under a light breeze on a Sunday afternoon, a gourmet break is needed on the terrace of the palace, on the side of the lake. While drinking a hot chocolate, all the voices suddenly stop: a pianist just arrived and starts playing Mozart’s Sonata in B flat major… This pianist is not Chilly Gonzales.

If you would like to meet the Canadian artist, reach a busy inviting bar where he’s playing, late at night. You would see the self-taught maestro improvising on an old piano of type saloon of the far-west, wearing grandpa slippers and making everyone sing in the room. If you could have a little chat with him afterwards, he would explain to you the link between music and the progression of male and female orgasms. He would eventually tell you how the cancellation of a flight ticket in Los Angeles allowed him to contribute to Daft Punk’s album “Random Access Memories”, or how he ended up doing a skit with Drake for The Canadian Victories of Music.

Chilly Gonzales is a piano Gangsta, breaking the codes of classical music, but he’s also a multi-awarded genius, having performed as a composer and interpreter on the biggest stages, breaking the Guinness world record of the longest solo-artist performance in one of them, in Paris, with slightly more than twenty-seven hours of live show…

His rebellious temper allows him to see the art first and foremost as entertainment, yet self-expression, eventually a tool of self-emancipation, but which shall not be taken too seriously. In the end, collecting an art form has never been vital: it creates a more or less lasting emotion, at most provoking reflection or serving as a temporary refugee, but its role remains humble: “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable” summarises British street artist Bansky. Gonzales, on his side, associates art with the magical moment when it is shared, as confessed in his 2018 interview for Huck: “For thousands of years, music was performed. It was just people playing in rooms for each other and creating connections. Then recording happened and the focus shifted to making these sort of definitive versions that exist forever, which performance will always be compared to. I think that gave people the illusion that music could be something different than performance. And of course, there was also an infrastructure, a business built around it, which attracts people who want to make a living from it – reinforcing this illusion of what music is: “We make permanent records.” It’s why a record is called a record!” Behind the word “entertainment” is “sharing”, “intelligence having fun”, to paraphrase Einstein, and “creating a connection”, which is far from being negative…

Besides the entertaining dimension, those “who think differently” often have a profound inner being: under the clownish surface, the turbulent Gonzales, like most innovating troublemakers, is also capable of the deepest artistic expression, as sensed in his intimate “Solo Piano” trilogy, unfolded in two decades, or in his 2017 “Room 29” with Jarvis Cocker. It is therefore no surprise that while not into electronic music at all, Gonzales fell for the abyssal album “Consumed“, which he only discovered in 2018, on the occasion of its 20th-anniversary re-edit.

In a 2018 interview for Ottawa Showbox, Gonzales said: “I still like to listen to music that supposedly has nothing in it, but if you take the microscope deep enough, you’ll find storytelling, you’ll find theme and variation, tension and release, question and answer, the hero’s journey.” This is somehow what must have been at work in his mind while listening to “Consumed.” He instantly visualised the gaps where he could add some jazzy piano notes and the idea became a project. He communicated it to his friend Tiga, a notorious Canadian remixer and producer, label owner of Turbo Recordings.

It happened that Tiga knew Richie Hawtin from the nineties and called him to propose the exciting plan. Gonzales made it clear that it would not be a remix, but that it would rather be – in his own words – “one composer instinctively reacting to – and finding space within – another composer’s already completed work which he adores.” Hawtin, on his side, accepted the condition to take care of the final mixing.

Such a project was very risky on paper and required great openness from both sides: “Consumed” is a pharaonic monument, whose rework can potentially divide the audience, with the complaints of the purists on the left, and the congratulations of the loyal fans on the right. For Richie Hawtin, the twenty-four years of time that separate him from the 1998 release somehow made it less untouchable, and Gonzales, on his side, having discovered the album only recently, didn’t really have the pressure to retouch a monument on his shoulders. The global pandemic crisis, closing clubs worldwide, created the conditions to set the dancefloor-oriented techno aside and focus on some “consumed music”, reminding that both artists are first and foremost talented musicians.

It is worth remembering that our scene owes Richie Hawtin the very first hypnotic techno track: Teste’s “The Wipe“, produced in 1992 under the supervision of the techno stalwart on Plus 8 sub-label Probe Records. It was before Mika Vainio developed the “alienating repetition” in 1993, and before Robert Hood officially defined hypnotic techno as a repetition “stripped-down at its core”, in 1994.

“Consumed” was revolutionary for adding textured atmospheres, which then directly influenced the Italian hypnotic techno artists. Claudio PRC, for instance, confessed to us that his adventures and research into sound started out of Plastikman’s early works.

“Consumed in Key” will not please everyone, but on our side, we have particularly enjoyed it, for its peaceful and beautiful minimalism. Dycide was one of the first artists to add piano notes in the deep hypnotic techno, giving an elegant touch to it, such as in the mesmerising track “Adytum“. We are therefore maybe already conditioned and delighted that a high calibre such as Chilly Gonzales also played this card.

While we would usually summarise the vibe of an album, we can’t help here but to share what we have felt, track after track, maybe also because this is our last review…

Gonzales’ instinctive reaction to Hawtin’s production is instantly perceptible within the opener “Contain (In Key)”. From the first strike of the piano keys, the melancholy that is brought forward in the piece hits home. The groove retained from Plastikman’s 1998 original combined with a perfect balance of bluesy piano gives the track a newfound character. Compositionally, but also in the way the sound design allows for elements to play between foreground and background, a marriage of past and present occurs. As Gonzales comments, this differs from being a remix, creating a conversation – a dialogue of distinct personalities coming together.

“Consume (In Key)” leaves the listener in a comfort zone for a while, creating a deep dive into that familiar dense bassline. It doesn’t take long before light optimistic piano playbacks insert into the track. The culmination begins when unhurried original hypnotic patterns give way to Gonzales’ melancholic acoustic solo. When the piano notes are harmonising with the characteristic intense bass and synths layers, the track offers a completely new perspective, reflecting scientific and melancholic shades under the prism of minimalistic techno sound. The new experience is provided by synergy and consumed by the listener. However, the deeper “Consumed” experience comes afterwards…

It is worth noting that although Gonzales’ input is not present or as audible in all tracks, such as in “Passage In (In Key)”, the format of the album was retained. While preserving the poetic flow which builds up from one track to the other, this also asserts one of the many elements which made the original 1998 release important: the producer’s storytelling capacity.

“Cor Ten (In Key)” sends a warm welcome with its instrumental opening, letting the initial sounds slowly unfold. The piano unobtrusive flows along the entire track from improvisation to a repetitive pattern, shifting the balance of the composition but still leaving moments to become saturated, respecting the stylistic spirit of the 1998 album.

With “Ekko (in Key)”, the introduction of further instruments such as the violin facilitates the dialogue’s continued evolution, highlighting Gonzales’ skills as a “sad music genius” – one of which is knowing when to add new layers of sound to further emphasise an emotional twist. The way this transforms the track’s pace is also rather fascinating. The tension in the original work seems to simmer down with the added instrumentality, creating meditative suspense. Similarly, when Hawtin’s composition leans towards a more atmospheric one, Gonzales’ sonic input at times contrasts, drawing on that atmosphere to escalate it to another realm.

“Converge (In Key)” has been hit by a message of hope, through the transition from dark to semi-light motifs. Gonzales enhances the condition with angelic playbacks and nervous piano play, which accompanies the composition until its conclusion.

Echoing – although categorising it as such might be simplifying – “Locomotion (In Key)” is another significant compositional approach. The way the instrumentalisation responds to the original production develops its dynamism, widening the expanse of the sonically drawn landscape.

Then, manipulative piano notes, coming into the spotlight and providing an unsettling mood, are covering “In Side (In Key)”. Hypnotised by the creative loops, the mind can release through the warm acoustic sound in the end. Gonzales picks out the melodies – the keys – transforming the track into different shapes within the framework of one composition, preserving the original atmosphere.

“Consumed (In Key)” is the climax of the album, which has more to do with its reference than with its energy or intensity: the 1998 original version “Consumed” remains one of the most important works for the hypnotic techno generation, causing a certain enthusiasm – if not urge – to discover the rework. Listening to the entire album closer, from one track to the other, exposes the piano progressively becoming more complex. In “Consumed (In Key)”, undertones make the bass lift off sublimely. The way the percussions and acid hues soar as notes are played rapidly, flowing into one another, results in a breathtaking journey. The track undoubtedly comes as another example of interpretation, which enriches an original work on a kaleidoscope of levels.

Finally, “Passage Out (In Key)” closes the circle opened by “Passage In (In Key)”, in a more dynamic mastering, resulting in a deeper yet more exhilarating emotional response. The dark and mysterious enveloping synth pads release the tension and harmoniously conclude the album. It somehow emphasises the cooperation of the two artists, with respect to the iconic original album.

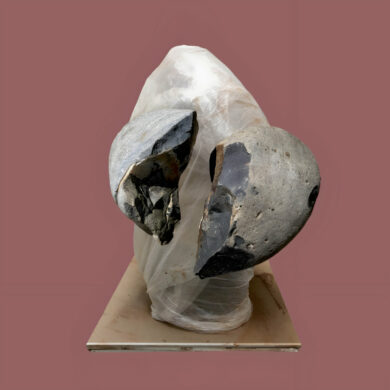

For us, “Consumed In Key” succeeded in the reconversion, bringing a certain modernity and elegance to the original version. From the edits to the artwork, which smartly inverts the colours to create a piano key, the minimalism is well preserved and pictured. The peace coming out of the journey works for the caring listener, who could also appreciate it while walking under a light breeze on a Sunday afternoon…

WRITING BY: TINA CAMILLERI, VADIM UKHANOV AND CEDRIC FINKBEINER | 4 APRIL 2022